Richard S. Ehrlich: A Letter From Turkey

A Letter From Turkey

by Richard S. Ehrlich

All Photos © copyright by Richard S. Ehrlich

Click for big version

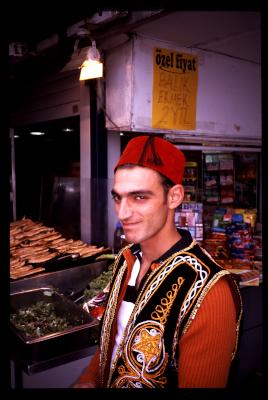

ISTANBUL, Turkey -- Some restaurants and places for tourists, including this grilled food outlet at the Eminonu port of Istanbul, adorn staff with a fez to create a bit of exoticism.

ISTANBUL, Turkey -- The cylindrical "fez" hat, with its dangling black tassel, provokes feelings of resentment, humiliation and grim memories of repression among many proud, nationalistic Turks.

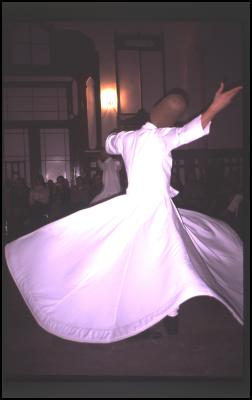

Another traditional symbol of Turkey, the white-robed Whirling Dervishes and their 700-year-old mystical Sufi brand of Islam, conjure up different responses, evoking a confused mix of suspicion and admiration.

Click for big version

ISTANBUL, Turkey -- Turkey eased its ban on Whirling Dervishes, and now allows performances, including this appearance by the fabled Galata Mevlevi group.

Welcome to Turkey, physically split between Europe and Asia by the Bosphorus Strait which now hosts expensive real estate along its shores amid seafood restaurants, a modern art museum, and lovingly restored mansions.

This East-meets-West crossroads hopes to join the European Union.

Turkey's new generation is becoming increasingly hip and globalized.

Islam competes to survive.

Young foreign tourists boast to awe-struck Turks about beer bongs and Western girls, but someone discreetly clicks off the radio's rock music when the neighborhood mosque's muezzin calls faithful Muslims to prayer via minaret-mounted electric loudspeakers.

The Ottoman Empire and its ruling, turbaned, Muslim sultans are frequently condemned as exploitative oppressors, defeated by independence fighters led by Mustafa Kamal Ataturk who created modern Turkey in 1923.

Click for big version

ISTANBUL, Turkey -- Mustafa Kamal Ataturk's fierce-eyed portrait forms a puzzle, on sale in a shop selling games. Ataturk's secularist cultural revolution banned the fez, the Whirling Dervishes, and other behavior he perceived as Islamic fundamentalism.

Ataturk's secularist cultural revolution banned the fez, the Whirling Dervishes, and other behavior he perceived as Islamic fundamentalism, backward rituals, and other hurdles to liberation.

Today, belly-dancers and less risque entertainers add "Ottoman cuisine" to their live shows, to attract tourists.

Hotels, restaurants, and souvenir shops include the title "sultan" in their name to create a bit of exoticism.

But a simmering bloody struggle, between Islamists and secularists, vexes Turkish society and often kills people on both sides.

Amid the violence, courts barred women wearing Muslim headscarves in public schools and government offices.

And the fez, now legal, is still widely despised.

"During the Ottoman Empire, the fez was worn by fundamentalist Muslims who were against democracy and Turkey as a republic," said businessman Mehmet Dasdeler in an interview in Goreme, in the heart of Turkey, 750 kilometers southeast of Istanbul.

"In 1925, Ataturk made a decree for people not to wear a fez. He changed our habits. Ataturk made all sorts of modern reforms," Mr. Dasdeler said.

"But in the last three or four years, money has changed people's ideals," and new fezzes -- made of cheap, bright-red velveteen -- are popular souvenirs on sale throughout Turkey for about five U.S. dollars.

An old, genuine, dark maroon fez, with a worn inner leather headband and three tiny air holes on top, could be purchased for about 50 U.S. dollars in a Goreme antique shop.

"No one is wearing a fez in all of Turkey. It has become stupid, silly. It's like an old memory," Mr. Dasdeler said.

Rasheed, an office worker in Istanbul's old Sultan Ahmet neighborhood, agreed.

"You see the fez worn in some restaurants or places for tourists. But if you ask Turks, some are very sensitive about it, because they think the West looks at Turkey as an old country, where people still wear the fez and who are not modern," Rasheed said.

"Actually, I don't like it when someone asks me about the fez. Turkey is not like that anymore," Rasheed said, becoming annoyed.

"During the Ottomans, the fez was mostly for people in the big cities who worked in the government, or the rich people," Rasheed's office colleague, Hassan, chimed in.

On trendy Akbiyik Street, Fez Travel uses the hat as its logo, plastered on tour buses and brochures.

"It is an easy symbol for tourists to recognize, and easy to say 'fez,' but actually it is still a problem for Turkey because of this whole thing about how the West looks at us, and how the European Union doesn't want us to join," Hassan said.

"We also don't understand why today in Hollywood, when you make a movie, you still show the people wearing a fez."

Cemeteries at some mosques display old tombstones topped by a chiseled fez, identifying the deceased as member of the Ottoman elite.

Click for big version

ANADOLUFENERI, Turkey -- Cemeteries at some mosques, including this one at Anadolufeneri town where the Bosphorus meets the Black Sea, display old tombstones topped by a chiseled fez, identifying the deceased as member of the Ottoman elite.

Whirling Dervishes suffered a different fate.

After Ataturk died in 1938, Turkey allowed public performances accompanied by music, including by the fabled Galata Mevlevi group.

Most Dervishes are men. Women may whirl, but usually in a separate room.

Twirling individually while circling in a room -- representing planets revolving while orbiting the sun -- Dervishes imagine a rapturous unity with God.

Click for big version

ISTANBUL, Turkey -- White-robed Whirling Dervishes of the fabled Galata Mevlevi group, and their 700-year-old mystical Sufi brand of Islam, conjure up a confused mix of suspicion and admiration.

Poetry by 13th century Sufi mystic Maulana Jalaluddin Rumi, who founded the Galata Mevlevi Whirling Dervishes in central Turkey, is surprisingly popular among Americans and other foreigners enthralled by Rumi's words of love.

Rumi's major work, The Masnavi, also describes ancient "tyrannical" Jewish kings exterminating Christians, and God punishing "evil" Jews.

Counter-clockwise whirling dissolves the ego and creates "an intoxication of the soul...mercy, offering consolation to those under tyranny," Rumi's Galata Mevlevi Whirling Dervishes said in a written statement before a performance in Istanbul.

A Dervish's extremely tall, conical, honey-colored, wool or camel-hair fez, "symbolizes a tombstone of the ego," the Mevlevis said.

A discarded black cloak represents the ego's "tomb."

The billowing white robe is the ego's "shroud."

"Be like me and know. Whether in light or darkness, until you have been like this, you can't completely know love," the Galata Mevlevi Whirling Dervishes said.

Osama bin Laden and his fellow Saudi Arabian Wahhabi Muslims condemn Sufis as liberal, pacifist deviant Muslims.

"I have some Turkish friends who are Whirling Dervishes, but they are doing it in performances for money. I don't know anyone doing it to get clean inside. They are just doing it as a job," said Mr. Dasdeler.

"There are not many Sufis in Turkey. There are more Sufis in America. Those [Galata Mevlevi Whirling Dervish] guys in Istanbul are real. They are Sufis.

"But when you become a Sufi, you have to give up your business and be clean about everything. You don't work for money, you work for God."

Copyright by Richard S. Ehrlich, a freelance

journalist who has reported news from Asia for the past 27

years, and co-author of the non-fiction book, "HELLO MY BIG

BIG HONEY!" -- Love Letters to Bangkok Bar Girls and Their

Revealing Interviews. His web page is

http://www.geocities.com/asia_correspondent

Eugene Doyle: BBC Goes Full Goebbels In Support Of Israeli Soccer Hooligans

Eugene Doyle: BBC Goes Full Goebbels In Support Of Israeli Soccer Hooligans Binoy Kampmark: They Were There First - Election Denialism, The Democratic Way

Binoy Kampmark: They Were There First - Election Denialism, The Democratic Way Martin LeFevre - Meditations: Self-knowing Is The Gateway To Liberation And Transmutation

Martin LeFevre - Meditations: Self-knowing Is The Gateway To Liberation And Transmutation Alastair Thompson: Google's Support For Democracy And Media In NZ | Part 1 - The Digital Media Bargaining Bill, NZME, STUFF & Google

Alastair Thompson: Google's Support For Democracy And Media In NZ | Part 1 - The Digital Media Bargaining Bill, NZME, STUFF & Google Binoy Kampmark: The Remembrance Day Amnesia Racket

Binoy Kampmark: The Remembrance Day Amnesia Racket Gordon Campbell: On The Crown’s Sorry Excuse For An Apology

Gordon Campbell: On The Crown’s Sorry Excuse For An Apology